INDIA Food & Culture in South Asia

INDIA

INDIA

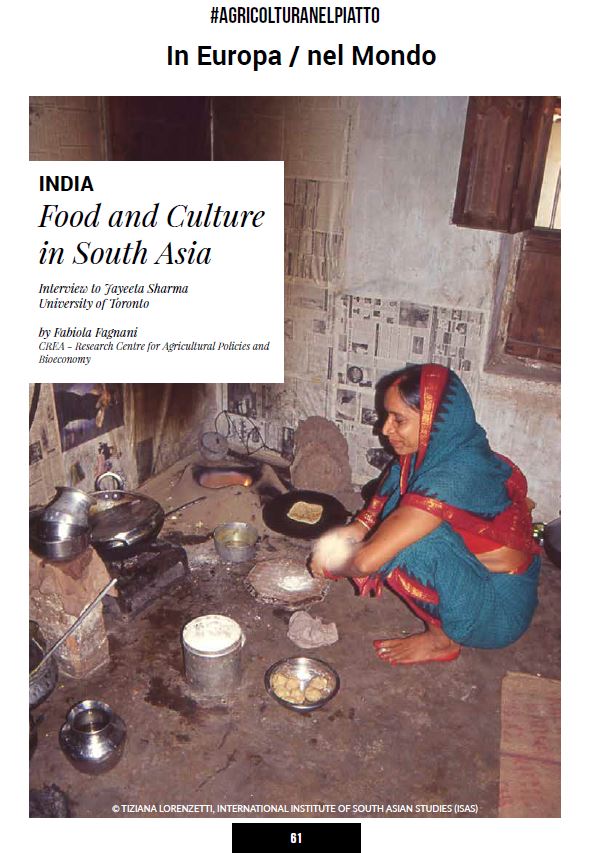

Food and Culture in South Asia

Interview to Jayeeta Sharma , University of Toronto

by Fabiola Fagnani

CREA – Research Centre for Agricultural Policies and Bioeconomy

RRN MAGAZINE n. 5, 2018, pp. 61- 63

Jo (Jayeeta) Sharma is an Associate Professor of History and Food Studies at the University of Toronto, Canada. She is the author of EmpirÈs Garden: Assam and the Making of India, which examines tea plantations and labour migration in the British Empire. She is on the Editorial Board of Global Food History and the Editorial Collective for Radical History Review. She is currently living in Torino and will be lecturing about South Asian foodways at the Università di Scienze Gastronomiche (as visiting professor) at Pollenzo, Italy.

Jo (Jayeeta) Sharma is an Associate Professor of History and Food Studies at the University of Toronto, Canada. She is the author of EmpirÈs Garden: Assam and the Making of India, which examines tea plantations and labour migration in the British Empire. She is on the Editorial Board of Global Food History and the Editorial Collective for Radical History Review. She is currently living in Torino and will be lecturing about South Asian foodways at the Università di Scienze Gastronomiche (as visiting professor) at Pollenzo, Italy.

Since you are a historian of food and culture, the question I would ask you is how the relationship between agriculture,food, way of life and local conditions in South Asia developed over time and what was the social and cultural impact

Like every part of the world in all historical times especially in the rural areas, people were very much subsisting on what they grew in the localities. So the two broad divisions in South Asia would have been the wheat eating zones and the rice eating zones. In the areas that cultivated wheat the main staple food would have been different kinds of flatbreads and in the rice eating zones boiled rice and other kinds of dishes made from rice were the staple. But in both regions the common kind of other dish which would have been grown is lentils, different kinds of lentils or dal. So think of a table where you have grains depending on the local conditions, so the connection between ecology and agriculture is that: in one area the bread would be eaten with lentils, vegetables, meat and so on and in another area the focus would be more on rice products. Some other examples I can give on agriculture, and what is produced is very influential. In my own area in North East India, which is called Assam, till the late 19th century most people had very limited access to salt. Salt had to be imported from other regions of India or sometimes from Tibet. So entire category of local dishes developed which used in fact a salt substitute. It was the shoots of the banana tree, they were burnt and the ash was used as a salt substitute.

This became a very specific kind of dish called Khar which is unique to this locality because of this very specific situation. The agriculture comes in: in this area there is one of the biggest rivers in the world the Brahmaputra River and there are many smaller rivers, so fish was abundant. People grew rice. So the staple dishes were fish and rice. Another local specificity is that in the western part of India, the region of Rajasthan which is a dry area, so there on desert ecology they were able to base the standard plate on some kind of flatbread made of wheat, and many kinds of dried lentil products.

So I would say that in the mid 19th century most people diet was based on very localized products and was very connected to what

was grown in the local area. This has had its impact even now. Basically in any part of South Asia you can buy rice or wheat or

whatever you want but in areas like the Punjab, in Northern India

there are people still predominantly eat roti, chapati, flatbreads.

And how did the international eating habits influence the local food markets in South-Asia?

I think it’s not just international habits but it’s also modernization and technology to influence food market.

In my childhood, I grew up in the 1970’s, when I lived in the region of Assam which is a peripheral region,things came on trains from quite a long distance. But there were certain vegetables which we did not know at all even then. The reason is because they were not grown in our region and they were vegetables that were not part of the cultural life of the people and even when they came into the diet: cauliflower, potatoes, all these were introduced, and of course many of them were not native, during the British colonial times and it took some time for them to get popular. So what happens is that some vegetables became very popular across the entire subcontinent and life of mountain regions communities was transformed with the availability of potato. Mountain potatoes varieties were introduced and those were changes in agriculture. Local peasants adopted and transformed those areas.

From the second half of the 19th century onwards potatoes, onions and garlic allow people to bring some more calories or more nutrition and some more variety into their diet and they also start being cultivated in different regions so they’re added to the agricultural profile. There is a big difference between the big cities, and even the smaller towns, and certainly between the different regions. So if you look at the map of India, in those regions that are more in the interior the connection between agriculture, local conditions, local cultural preferences has continued in many ways. While the young people, and this is where internationalization comes in, all over the world now want to have pasta.

In Italy we pay close attention to the food safety because of health problem, to sustainable agriculture and so on. Is there an attention to these points in South Asia?

Many of the things in the crops were organic simply because small farmers were not able to afford the best science. But then we had the so-called Green Revolution which allowed the famines. Green Revolution of the 1970s made food security in terms of enough grains to supply the whole country but food insecurity remains because the distribution system and the class access has remained till date and this is the big failure in Indian social policy.

People are now getting aware of it. There is very little food regulation that works. And so now people are getting concerned about not only organic. Most of consumers especially in cities are getting concerned about adulteration, they concern that same vegetables might look beautiful but they may have been grown in contaminated ground. And there is no government organization that’s doing a good job of actually checking those. Spices are indispensable: every day meal every indian family will afford it will use some spices. Those spices were usually sold in shops. Consumers have discovered that the standards of regulation are there but the enforcement is not so good. And so some of the newspapers have run the tests and they have discovered, they say, the packaged spice has a lot of adulteration. Therefore, there is concern among consumers and that’s why people are trying to get a more expensive organic varieties.

So to sum it up, now there is attention to heritage. There are signs to going back and trying to bring back the skills that almost got lost. The concern about adulteration, about that we should be eating,more organic foods without pesticides and so on, that’s good but we should also look at making basic food available for everyone. So basically what I would say: we are concerned about the quality of the food, about sustainability but we should also pay attention to the food supply, food equity.